Today we are conducting our fifteenth annual Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony. As with most good programs, our Hall of Fame started with a good idea. Montgomery attorney, Terry Brown, who at the time was the immediate past-president of the Montgomery County Bar Association, and who died in December of 2016, wrote me a letter when I was Alabama State Bar President in 2001. He suggested that our association should establish an Alabama Lawyers’ Academy of Honor, essentially a Hall of Fame, recognizing Alabama lawyers who have achieved national or international renown and who have brought honor to themselves, the state of Alabama, and the legal profession. He also suggested that the Hall of Fame be located in the former Alabama Supreme Court Building which was sitting empty and unused.

In the fall of 2002, State Bar President Fred Gray appointed a Task Force to explore the feasibility of establishing an Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame. President Gray appointed me as Chair of the Task force to consider selection criteria and other issues. He hoped that we would make a quick report to the Board of Bar Commissioners and that an initial induction ceremony would take place while he was still Bar President in 2003.

As we all know, the proverbial “devil” is always in the details. The Task Force conducted research on existing Halls of Fame, studied positions both for and against “living” versus “posthumous” induction, and then we presented our recommendation. The report was made in 2003 and was approved by the Board of Bar Commissioners. Next, a Hall of Fame Selection Committee based on the recommendation had to be appointed, nominations were solicited, and our first group of inductees were finally selected for a ceremony held in May of 2005 for our 2004 honorees. Now we are conducting our fifteenth ceremony being held in May of 2019 for our 2018 honorees. With these inductees we have now selected 70 attorneys from among all the lawyers in the 200-year history of the State of Alabama.

Over the years we have recognized judges, both appellate and trial, both Federal and State, military heroes, public servants, law professors, Governors, Senators, Congressmen, Mayors, a Vice-President of the United States, and a Speaker of the House of Representatives. But our largest single demographic is the group of lawyers, all outstanding individuals, who have labored in the field of private practice. All of our lawyer-inductees are the true giants, the mentors, and, yes, the heroes of our profession.

Inductees into the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame must have had a distinguished career in the law. This could be demonstrated through many different forms of achievement, leadership, service, mentorship, political courage, or professional success. Each inductee must have been deceased at least two years at the time of their selection. Also, for each group of inductees, at least one honoree must have been deceased a minimum of one hundred years in order to give due recognition to historic figures as well as the more recent lawyers of the state.

Our twelve-member selection committee consists of the immediate past-president of the Alabama State Bar, a member appointed by the Chief Justice, one member appointed by each of the three presiding Federal District Court judges of Alabama, four members appointed by the Board of Bar Commissioners, the Director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, the Chairman of the Alabama Bench and Bar Historical Society, and the Executive Secretary of the Alabama State Bar. The committee meets annually to consider the nominees and to make selections for induction. Now at this time I ask that the members of the selection committee stand and be recognized by the audience today.

So please consider making nominations for our Hall of Fame. The nomination form and instructions can be found on the Bar’s website. I say this each year, but remember, great lawyers cannot be considered for induction into the Hall if they have not been nominated.

Here are this year’s inductees.

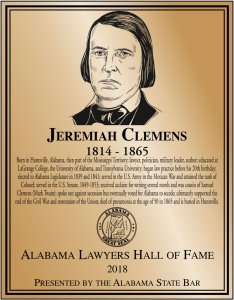

- Jeremiah Clemens (1814 - 1865)

-

Born in Huntsville in 1814, Jeremiah Clemens was the son of a merchant who had relocated to Alabama from Kentucky during the early settlement of the Tennessee Valley. Jeremiah attended La Grange College and the University of Alabama, where he graduated in 1833. Following a year of legal studies at Transylvania College in Kentucky, he established a law practice in Huntsville and married Mary L. Read. The couple had one child, Mary Read Clemens Townsend.

Born in Huntsville in 1814, Jeremiah Clemens was the son of a merchant who had relocated to Alabama from Kentucky during the early settlement of the Tennessee Valley. Jeremiah attended La Grange College and the University of Alabama, where he graduated in 1833. Following a year of legal studies at Transylvania College in Kentucky, he established a law practice in Huntsville and married Mary L. Read. The couple had one child, Mary Read Clemens Townsend.In 1838 Clemens received appointment as U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, and two years later he won his first elected office—a term in the Alabama Legislature. Clemens interrupted his legislative service in 1841 to lead a company of volunteers to Texas to resist Mexican army incursions. He would return to the border in 1847 to fight in the Mexican-American War, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel.

An 1848 bid for Congress was unsuccessful, but Clemens’ former colleagues in the legislature elected him the next year to the U.S. Senate, where he served until 1853. He spent the late 1850s in Memphis, where he published a newspaper and continued his nascent career as a novelist. Interestingly, Jeremiah Clemens was a cousin of Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain.

Clemens was back in Madison County, Alabama, in time to represent the county in Alabama’s 1861 secession convention. Like most north Alabamians, he opposed immediate secession in response to the election of Abraham Lincoln and his hostility to the expansion of slavery. Clemens favored patience and urged his fellow delegates to slow their march toward disunion.

Representing the cooperationist faction, Clemens called on the convention to postpone action until the slaveholding states could determine a course forward in unison. He also favored a statewide referendum on the question of secession, but was unsuccessful on both counts. When it became clear that the secessionists would prevail, Clemens ultimately voted for the ordinance as a sign of unity and dedication to his state.

Back at home in the Tennessee Valley, Clemens and his neighbors faced the eventuality that had shaped their anti-secession sentiments—quick exposure to the realities of war. Union forces occupied north Alabama in 1862, and Clemens declared his allegiance to the U.S. Through the rest of the war, he promoted Unionist sentiment in the area, building relationships with Federal officers, presiding over a Unionist gathering, and offering advice to the Lincoln administration on how to reassemble the divided nation.

Clemens apparently aspired to a federal appointment at war’s end, but he died of pneumonia on May 21, 1865, barely fifty years old. A lawyer, legislator, soldier, and stateman who sought to prevent civil war and then to heal its effects, Clemens joins other extraordinary attorneys in the Alabama Lawyers Hall of Fame.

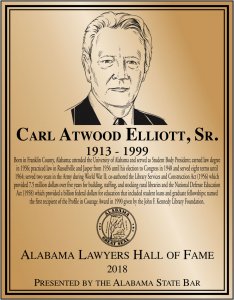

- Carl Atwood Elliott (1913 - 1999)

-

Carl Atwood Elliott was born in rural Franklin County and was the valedictorian of Vina High School when he was 16 years old. This was in the years of the Great Depression, so few expected him to attend college. Not one to let poverty impede him, he convinced President George Denny at the University of Alabama to allow him to work odd jobs on campus to pay his educational expenses, at one point living in an abandoned observatory on the grounds to save money.

Carl Atwood Elliott was born in rural Franklin County and was the valedictorian of Vina High School when he was 16 years old. This was in the years of the Great Depression, so few expected him to attend college. Not one to let poverty impede him, he convinced President George Denny at the University of Alabama to allow him to work odd jobs on campus to pay his educational expenses, at one point living in an abandoned observatory on the grounds to save money. He received his undergraduate degree in 1933, and as a law school student ran for Student Government President. With a coalition of out of state students and women, he was the first person to defeat the Machine and in 1936 completed his law degree as President of the Student Body.

Carl moved to Jasper and began representing coal miners and their families, foreshadowing his long career of fighting for Alabama’s poorest and most disadvantaged. After a stint in the military from 1942 to 1944 he came home and was elected local judge in Jasper. He then ran for Congress, unseating a long time politician, Carter Manasco. He represented the 7th Congressional District and in 1956 authored the Library Services Act which brought mobile libraries to rural Americans.

In 1958, Russia, with Sputnik, had taken the lead in the space race, something the U.S. simply was not going to tolerate. So, in 1958, believing that education had provided his ticket to escape poverty, Elliott co-authored the National Defense Education Act. The NDEA not only improved science, foreign language and technology education nationwide, it provided low interest loans for needy students. This law has been continuously extended and it is estimated that more than 20 million vocational, college and graduate students have received student loans as a result of the NDEA.

Despite being quite progressive in his views on race relations, he was an astute politician, and knew to be re-elected to Congress he had to publicly take a different stand. In 1956 he signed the Southern Manifesto in opposition to racial integration of public places. Believing that federally decreed desegregation begat violence, he voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 and 1964. But despite these votes, and being aware of Elliott’s true leanings, the Democratic leadership appointed Elliott to the House Rules Committee, knowing Elliott would vote to overcome deadlocks on the committee and thus advance President Kennedy’s agenda.

But his work on the Rules Committee and the effect of the 1960 Census were Elliott’s political undoing. From a relatively liberal district, Elliott won reelection in 1960, but the 1960 Census cost Alabama a Congressional district. The Alabama legislature created a plan that in 1964 all nine sitting Congressmen would run at large and eight winners would take seats in Congress. Governor George Wallace, fearful of Elliott’s influence, marshaled all his political forces against him, and Elliot was not reelected to Congress. However, continuing to hold strong in his convictions, he cashed in his Congressional pension and ran against Lurleen Wallace in the 1966 Democratic gubernatorial primary. Lurleen was place-holding for her husband George who, at that time, could not succeed himself. Elliott supported Federal Assistance to the needy, improved education and racial tolerance. He was confronted with bomb threats, defaced billboards and Ku Klux Klan protests at his rallies. Lurleen Wallace won. Elliott finished third.

Elliott never ran for office again. In the late 1960’s he was appointed to the President’s Library Commission and as a Deputy to the Commerce Department. He returned to the practice of law, wrote for area newspapers, and authored five historical volumes of the Annals of Northwest Alabama and seven volumes on the history of local coal miners.

But that is not the end of the story. In 1990 Parade Magazine did a cover story announcing the John F. Kennedy Library’s Profile in Courage Award. Candidates for the award had to be public officials who had made courageous decisions despite political and personal risks. In three weeks, more than 5,000 nominations were generated nationwide. From all of these nominees, Carl Elliott was chosen to receive the first Profile in Courage Award.

Elliott’s autobiography, The Cost of Courage, The Journey of an American Congressman, was edited by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. His name lives on in the Carl Elliott Regional Library in Jasper, the Carl Elliott House Museum and the Carl Elliott Society at the University of Alabama. But what is his legacy? His legacy lives on in those 20 million people who were able to receive their vocational, college, graduate school, or even law degrees as a result of his vision, his selflessness and hard work, and those 20 million have gone on to continue to change our world for the better.

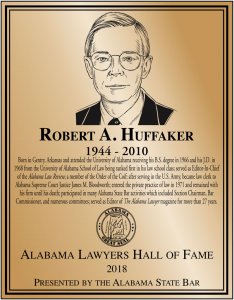

- Robert Austin Huffaker, Sr. (1944 - 2010)

-

Robert Austin Huffaker, Sr. earned recognition as a “lawyer’s lawyer” early in a career that spanned 40 years. He graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law in 1968, first in his class, Editor-in-Chief of the Alabama Law Review and Order of the Coif. He served his country as a U.S. Army 1st Lieutenant until 1970.

Robert Austin Huffaker, Sr. earned recognition as a “lawyer’s lawyer” early in a career that spanned 40 years. He graduated from the University of Alabama School of Law in 1968, first in his class, Editor-in-Chief of the Alabama Law Review and Order of the Coif. He served his country as a U.S. Army 1st Lieutenant until 1970.His distinguished career began as law clerk to Justice James Bloodworth on the Supreme Court of Alabama, after which he entered private practice in 1971 with the Montgomery firm of Rushton, Stakely, Johnston & Garrett P.A. He remained a firm shareholder until his death in 2010.

He was born in Arkansas; however his father’s military career brought the family to Dothan, Alabama, where Robert established an outstanding academic record at Dothan High School and where he was on the school’s excellent golf team. He continued to enhance his academic record at the University of Alabama, earning a straight-A grade point while graduating with a bachelor’s degree in 1966. It was his law school performance, while attaining his Juris Doctor degree, that led both faculty and classmates to acknowledge he possessed a rare talent for the study of law.

Classmate Charles Gamble, who would later serve as a Professor and Dean of the school of law, described Robert as having a combination of talent that only top-tier legal advocates possessed. “His ability to think effectively through complex legal issues was complimented by the capacity to express those thoughts effectively in writing.”

Robert was held in high esteem by those with whom he practiced, as well as by those practitioners who were on opposing sides of a legal issue. He was an honorable gentleman whose quiet dignity and decency of manner were character traits respected and admired by all who knew him. He was slow to anger and quick to laugh. Robert was generous with his time and talents.

He accepted appointment as Editor of The Alabama Lawyer, the official periodical of the Alabama State Bar, in 1983 when it underwent a drastic format change and an increased frequency of publication. This was a wholly volunteer position and he served with an appointed volunteer Board of Editors.

Robert served in this position for 27-plus years, until his untimely death. Under his guidance and meticulous care, he was, in essence, the steward of the history of the state bar, by which we have measured the pulse of the legal profession for more than a quarter of a century, a period in which the legal profession, the law and the state bar experienced growth and substantial change. Robert’s generosity of service was recognized when he received the William D. “Bill” Scruggs, Jr. Service to the Bar Award. A frequent contributor to The Alabama Lawyer, while lauding Robert’s efforts, described him as a “writer’s editor.”

The magnitude of Robert’s talents, as well as his gift to our profession, is made the more remarkable by the fact he was an active and effective trial practitioner and appellate advocate whose counsel was sought both within and without the State of Alabama. While serving in the demanding Editor’s position, he also served in other professional volunteer activities.

Robert’s devotion to his profession was exceeded only by that to his wife, Kitty, and his two lawyer sons, Austin and Lee, and their families.

The induction of Robert Austin Huffaker, Sr. into the Alabama Lawyers Hall of Fame memorializes a career and life well lived and the BEST of professionalism within the Alabama State Bar and the cause of justice in our society.

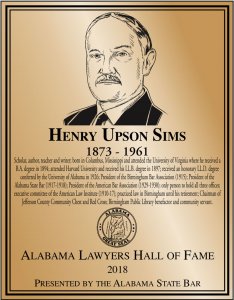

- Henry Upson Sims (1873 - 1961)

-

Henry Upson Sims was born in Columbus, Mississippi on June 27, 1873. He was the son of William Henry and Elizabeth Louisa (Upson) Sims. His father served as the Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi and Assistant Secretary of the Interior during President Cleveland’s administration from 1893-1897. Upson County Georgia was named for his mother’s grandfather, Stephen Upson, a Georgia lawyer, legislator, and trustee of the University of Georgia. Henry was educated at the University of Virginia and Harvard where he received his law degree. He came to Birmingham in 1898 and practiced law there until his retirement more than fifty years later.

Henry Upson Sims was born in Columbus, Mississippi on June 27, 1873. He was the son of William Henry and Elizabeth Louisa (Upson) Sims. His father served as the Lieutenant Governor of Mississippi and Assistant Secretary of the Interior during President Cleveland’s administration from 1893-1897. Upson County Georgia was named for his mother’s grandfather, Stephen Upson, a Georgia lawyer, legislator, and trustee of the University of Georgia. Henry was educated at the University of Virginia and Harvard where he received his law degree. He came to Birmingham in 1898 and practiced law there until his retirement more than fifty years later.Mr. Sims was a scholar, author, and community servant. He loved books throughout his life and was one of the most generous benefactors of the Birmingham Public Library, donating $50,000 in 1922 in memory of his father for the purchase of books on science and technology. A white marble plaque in the Linn-Henley Research Library building commemorates this generosity. He was interested in many far-ranging subjects and he wrote on historical, legal, and religious topics.

Henry Upson Sims was a leader of the Bar. He served as President of the Birmingham Bar in 1915, President of the Alabama State Bar in 1917-1918, and President of the American Bar Association in 1929-1930. He is the only lawyer in the history of Alabama to lead his local, state, and the national bar association. He also advocated for improvements in the law by serving on the executive committee of the American Law Institute from 1910-1917, and he served as the annotator for Alabama of the Restatement of Contracts, 1937, and the Restatement of Property, 1946.

Mr. Sims loved his community and extensively volunteered his time in community service. He was chairman of the Jefferson County Community Chest (predecessor of the United Way), chairman of the Jefferson County Red Cross, and he even served on the national central committee of the American Red Cross from 1930-1942. He was also a director of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce.

Henry Upson Sims received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Alabama. He was a member of several academic honorary fraternities, including Phi Beta Kappa. Mr. Sims is a sterling exemplar of a lifetime of hard work and service. He died in Birmingham on October 31, 1961. He is honored now with induction into the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

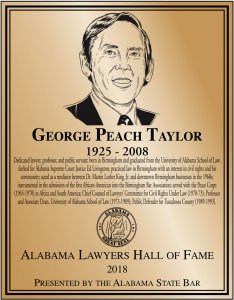

- George Peach Taylor (1925 - 2008)

-

George Peach Taylor was born in Birmingham, Alabama on September 16, 1925. He attended Ramsay High School, graduating at the age of fifteen. Taylor began studies at Birmingham-Southern College on a Phi Beta Kappa scholarship, but in 1942 joined the U.S. Navy, entering the V-12 College Training Program, a program designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers during World War II. He was assigned to Midshipman School at the Chicago campus of Northwestern University from which he graduated seventh out of a class of over seven-hundred students. Afterwards, Taylor was assigned to Scouts and Raiders School, the forerunner to the Navy Seals Program today, completing his training in 1945. He attended Advanced Naval Intelligence School in New York City and was assigned as Operations Officer of the Philippines Sea Frontier in Manilla. In 1946, after receiving his discharge from the U.S. Navy, Taylor returned to Birmingham-Southern from which he graduated in 1948 after earning numerous honors. Taylor began law school at the University of Alabama in 1948, serving as President of the Student Body from 1950-51. He was a member of the University of Alabama Law Review and the 1951 Moot Court Competition Winner, graduating in 1951 in the top ten percent of his class.

George Peach Taylor was born in Birmingham, Alabama on September 16, 1925. He attended Ramsay High School, graduating at the age of fifteen. Taylor began studies at Birmingham-Southern College on a Phi Beta Kappa scholarship, but in 1942 joined the U.S. Navy, entering the V-12 College Training Program, a program designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers during World War II. He was assigned to Midshipman School at the Chicago campus of Northwestern University from which he graduated seventh out of a class of over seven-hundred students. Afterwards, Taylor was assigned to Scouts and Raiders School, the forerunner to the Navy Seals Program today, completing his training in 1945. He attended Advanced Naval Intelligence School in New York City and was assigned as Operations Officer of the Philippines Sea Frontier in Manilla. In 1946, after receiving his discharge from the U.S. Navy, Taylor returned to Birmingham-Southern from which he graduated in 1948 after earning numerous honors. Taylor began law school at the University of Alabama in 1948, serving as President of the Student Body from 1950-51. He was a member of the University of Alabama Law Review and the 1951 Moot Court Competition Winner, graduating in 1951 in the top ten percent of his class. His first job as a lawyer was as a law clerk for Chief Justice J. Ed Livingston of the Supreme Court of Alabama after which he was hired at the firm that later became Dominick, Fletcher, Taylor, and Yeilding. An interest in civil rights led him to become actively involved in the Jefferson County community. He was instrumental in the admission of the first African-American into the Birmingham Bar Association and acted as a mediator between Dr. Martin Luther King and downtown Birmingham businesses during the demonstrations there in the 1960s.

Having practiced law for thirteen years, Taylor, in 1965, joined the Peace Corps taking his wife, Mary Letta English Taylor and their four children George, Ann, Jarred and David to Sierra Leone, Africa, where he served as Deputy Director of the Peace Corps. One year later, Taylor was promoted to Director of the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone, serving in that capacity for two and a half years. He then moved to Washington, D.C. serving the Peace Corps in an administrative capacity. He later returned to the field. serving for two more years as the Corps’ director in Guyana.

In 1970, Taylor returned to the United States as chief counsel for the Mississippi office of

American Lawyers for Civil Rights Under the Law in Jackson, Mississippi. While there he prosecuted a civil damage suit, Burton v. Waller, against Mississippi law enforcement on behalf of students injured and killed by gunfire at a 1970 demonstration at Jackson State University.

In 1973, Taylor joined the faculty at the University of Alabama School of Law where he remained for 16 years. He taught criminal law, equity and trial advocacy serving as assistant dean during his time at the Law School. Under his stewardship, the Law School’s trial advocacy program grew to national prominence. During this time, Taylor also continued to actively practice law, including representation of state prisoners and mental health patients in lawsuits regarding conditions of confinement that set standards still followed today. In 1989, at the age of 64, Taylor embarked on yet another chapter in his career, becoming Public Defender for Tuscaloosa County, where he served until 1993, when he retired.

In 2001, George Peach Taylor was awarded the American Bar Association’s John Minor Wisdom Award for Service to Civil Rights and the Legal Profession, one of the highest honors that the ABA can bestow. In support of Taylor’s nomination to the award, Judge (later Justice) Robert B. Harwood, Jr. wrote, “Peach’s career has been of the sort that most of us aspired to achieve while we were in law school, but for which we lost total commitment as we made our way. He has dedicated himself to upholding and vindicating the rights of others and making our justice system available to everyone, regardless of financial or social stature. He truly is a humanitarian and I unreservedly commend his nomination to you.” The late Dean Thomas Christopher, under whom Taylor served at the Law School wrote, “reading his long list of assignments in public service…one sees a man who served well the Bar, and humanity – above all humanity. And he has done a thousand little acts as one who cares – sincerely cares.”

George Peach Taylor passed away on December 10, 2008 in Tuscaloosa without a doubt leaving this world a better place than he found it. The Bench and Bar of the State of Alabama is proud to induct George Peach Taylor into the Alabama Lawyers Hall of Fame.