Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic, the 2019 Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame induction ceremony scheduled for May 1, 2020 at the Alabama Supreme Court was postponed to March 11, 2022. We are pleased to recognize the new selectees of the Hall of Fame who represent the finest exemplars of the Alabama legal profession. These new inductees now bring the total number of Hall of Fame members to 75. We hope that all of their stories will serve to inspire the present and future citizens of Alabama.

- Clifford Judkins Durr (1899-1975)

-

Clifford Judkins Durr was born in Montgomery, Alabama, March 2, 1899 and died there on May 12, 1975. He earned praise as a highly principled lawyer as well as a public servant. He was also known as a devout man who worked tirelessly to serve his country and its Bill of Rights while providing support to his family.

Clifford Judkins Durr was born in Montgomery, Alabama, March 2, 1899 and died there on May 12, 1975. He earned praise as a highly principled lawyer as well as a public servant. He was also known as a devout man who worked tirelessly to serve his country and its Bill of Rights while providing support to his family.He was educated in Montgomery private schools and then attended the University of Alabama. He won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University where he received a law degree in 1922. Upon returning to Montgomery, he joined a local law firm. He also practiced law in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for a year having passed both the Alabama and Wisconsin bar exams. He would later join the prominent Birmingham corporate law firm of Martin, Thompson, Foster and Turner where he enjoyed the practice and was poised for a successful legal career. In 1926, he married Virginia Foster and they had five children. Both Cliff and Virginia had been born into prominent Alabama families.

Cliff would later accept, in 1933, a position with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in Washington, DC. He had been recommended for this position by his brother-in-law, U.S. Senator Hugo L. Black, at the beginning of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first term. This move led to a seventeen year residency in Alexandria, Virginia. He was a productive and innovative lawyer with the RFC for seven years until the position was ended.

He was then appointed to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). His work there began focusing on protecting the public interest rather than advocating for banking and broadcasting interests. At the FCC, he fought for public broadcasting free of advertising, and public channels for television.

During Mr. Durr’s last two years at the FCC, he became involved in the civil liberty issues, which came to mark his legal career. He resigned, in protest, from the FCC over the Federal Loyalty Oath Order in 1948 which he saw as an abuse to FCC’s employees’ rights. He established a private practice in Washington that focused almost exclusively on civil liberties issues.

Clifford Durr was devoted to his home state. Despite health issues and other obstacles, from the early 1950’s until he retired in 1964, he maintained a law practice in Montgomery, Alabama. He used his considerable skills to represent African-Americans (among whom was Mrs. Rosa Parks) and other civil rights litigants, many of whom could not pay a fee. This led to his social ostracism and economic suppression in his place of birth.

Mr. Durr’s civil rights work brought him accolades and invitations to speak at prestigious American Universities and at Oxford in his final years. Auburn University at Montgomery honors him annually with sponsorship of the Clifford Durr Lecture Series. An editorial in The Nation entitled “The Conscience of a Lawyer” lauded his professional skill and his inclination to conduct himself honorably no matter how difficult the situation. It is with great pride that Clifford Judkins Durr is inducted into the Alabama Lawyer’s Hall of Fame.

- Broox Gray Garrett (1915-1991)

-

Broox Gray Garrett was born in Grove Hill, Clarke County, Alabama on December 27, 1915 to Judge Coma Garrett and Margaret W. Garrett. He died on February 13, 1991.

Broox Gray Garrett was born in Grove Hill, Clarke County, Alabama on December 27, 1915 to Judge Coma Garrett and Margaret W. Garrett. He died on February 13, 1991.He received his undergraduate degree in 1937 and his law degree in 1939, both from the University of Alabama. He was admitted to the Alabama State Bar and began practicing law in Brewton, Alabama immediately. While at the University he was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Omicron Delta Kappa, and the Farrah Order of Jurisprudence (now the Order of the Coif).

After starting a practice in Brewton in1939, he enlisted in the U. S. Navy on December 8, 1941 and served until October of 1945 when he was discharged as a 1st Lieutenant. He returned to Brewton and practiced law until he retired in 1989.

From 1947 to 1953 Garrett served his community as Escambia County Solicitor. He was a member of the Brewton City Board of Education beginning in 1949 and served as Chairman of the Board from 1951 until his retirement in 1962. He was selected as a Fellow in the American College of Trial Lawyers in Washington, D. C. in 1973. And he was a member of the Alabama State Bar Board of Bar Commissioners from 1966 until 1989. He was elected Vice President of the Alabama State Bar in 1981 and became President after the untimely death of then President Harold V. Hughston. During his term as President, the Mandatory Continuing Legal Education Program became a function of the Alabama State Bar. Garrett later also served as President of the Alabama Law School Foundation.

As further evidence of his community service, Broox Garrett was a very active member of the First Baptist Church of Brewton as a Deacon and Trustee for many years. Also, he was a loyal supporter of the Democratic Party and served as a member of the State Executive Committee and Chairman of the Escambia County Democratic Party. And he served on the Board of Directors of the First National Bank of Brewton and became a Director Emeritus after his retirement.

Broox Garrett was an idealistic, successful lawyer and was greatly respected for his service, his legal abilities, and as a gentleman of the law. He was more than a lawyer’s lawyer. He was a people’s lawyer. The lawyers of Alabama now honor him as a member of the Alabama Lawyer’s Hall of Fame

- Henry Washington Hilliard (1808-1892)

-

Henry Washington Hilliard achieved recognition in a variety of endeavors during his life. He was a Southern lawyer, a college professor, an author, a translator, a Methodist lay minister, a Congressman, a Confederate military leader, a U.S. Ambassador, and a pivotal player in a national abolitionist movement in South America.

Henry Washington Hilliard achieved recognition in a variety of endeavors during his life. He was a Southern lawyer, a college professor, an author, a translator, a Methodist lay minister, a Congressman, a Confederate military leader, a U.S. Ambassador, and a pivotal player in a national abolitionist movement in South America.Born in North Carolina in 1808, Hilliard attended South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina), and read for the law under William C. Preston, a prominent lawyer and U.S. Senator. After completing his legal studies, Hilliard was admitted to practice law in Athens, Georgia, in 1829. In 1831, he was named Professor of English Literature at the newly founded University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. Three years later, he moved to Montgomery to practice law.

Hilliard was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1838. The same year, he became involved in the national Whig Party as a delegate to the 1838 Whig National Convention, and he served as a Whig presidential elector in 1840. In 1842, President John Tyler appointed Hilliard U.S. Chargé d’affaires to Belgium. After he returned to Montgomery in 1844, Hilliard was elected to Congress on the Whig ticket. While in Congress, he served as a Regent of the Smithsonian Institution. After serving his third term, Hilliard did not seek reelection, and he returned instead to his law practice.

Despite his legal training under William C. Preston, who was an outspoken advocate of nullification and states’ rights, Hilliard vigorously opposed secession during the years leading up to the Civil War. With his renowned oratory skills, Hilliard opposed calls for secession by William Lowndes Yancey and the Fire-Eaters. When Alabama seceded from the Union, however, Hilliard raised the 3,000-man Hilliard’s Legion in Montgomery, which later fought under General Braxton Bragg in Tennessee and Kentucky. At the end of 1862, Colonel Hilliard resigned his commission and returned to Montgomery and the practice of law. After the War, he moved to Augusta, Georgia, to practice law there.

In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes, who had been a Major General in the Union Army, appointed Hilliard to be U.S. Ambassador to Brazil. Hilliard developed a close relationship with Emperor Dom Pedro II and the two spent much time together discussing their shared love of classical literature, science and the Smithsonian Institution, democratic reforms, and the effects of the institution of slavery. Despite having been a slave owner himself and having represented proslavery interests in Congress, Hilliard vocally advocated for the abolition of slavery in Brazil. In a highly irregular move for a foreign diplomat, he gave a speech to the Brazilian Anti-Slavery Society, which was publicized throughout the nation and is credited with turning the tide in favor of abolition there. Years later, upon learning that Brazil had abolished slavery, Hilliard said that speech “was the most heroic act of my life, and I desire it to be remembered of me while I live and after my life has closed.”

We honor this Southern moderate who opposed the winds of division, but when the decision was made, stood with Alabama until the defeat of the Confederacy. Out of the lessons learned from the destruction of the South’s slave-based economy and culture, Henry Washington Hilliard took a bold risk to warn another nation of the calamitous perils of persisting on the same path of bondage, and in so doing, ended his life on a public note of personal redemption.

- Richard Taylor Rives (1895-1982)

-

Richard Taylor Rives was born in Montgomery on January 15, 1895. He was in the first graduating class at Sidney Lanier High School and was class valedictorian in 1911 at age 16. He attended Tulane University in New Orleans for one year but left school due to his family’s financial difficulties. In 1912 he began an apprenticeship in the Montgomery law office of Wiley Hill, a Rives family friend. With no college or law degree, Richard read the law and passed the Alabama Bar Exam in March 1914. He was admitted to practice law in Alabama at age 19.

Richard Taylor Rives was born in Montgomery on January 15, 1895. He was in the first graduating class at Sidney Lanier High School and was class valedictorian in 1911 at age 16. He attended Tulane University in New Orleans for one year but left school due to his family’s financial difficulties. In 1912 he began an apprenticeship in the Montgomery law office of Wiley Hill, a Rives family friend. With no college or law degree, Richard read the law and passed the Alabama Bar Exam in March 1914. He was admitted to practice law in Alabama at age 19.Rives joined the Alabama National Guard in 1914. He served overseas during World War I and was an officer in the United State Army from 1917 to 1919. He returned to Montgomery and practiced law with Hill’s firm from 1919 to 1947.

Richard Rives built a reputation as a great trial lawyer through his ability and hard work. He became active in Alabama politics. Rives was a leader in the Bar and served as President of the Montgomery Bar Association in 1939. He was President of the Alabama State Bar for the 1939-1940 term. During his year as President, The Alabama Lawyer began publication. He established his own law firm in 1947 which today is the Copeland Franco firm.

In 1951, President Harry Truman appointed Rives to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. While in this position Judge Rives took part in many landmark decisions, possibly the most memorable being Browder v. Gayle, which outlawed segregation in Montgomery’s bus system, ending the bus boycott sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks in 1955. His opinion in this case on a three-judge panel, which included Judge Frank Johnson, extended the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed the “separate but equal” doctrine in public schools. Browder applied the Brown case ruling to public transportation.

Judge Rives continued to serve on the 5th Circuit and, after its division, the subsequently created 11th Circuit, until his death in 1982. His decisions struck down segregation in schools, parks, housing, public facilities, jury selection, higher education, voting, and legislative reapportionment. As a Montgomery native Judge Rives showed great courage in rendering decisions which ran counter to segrationist traditions in the South despite experiencing personal reprisals such as social ostracism, hate mail, threats, and even the desecration of his deceased son’s grave.

Though not a college or law school graduate, Judge Rives was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Notre Dame University in 1966 and an honorary degree from Cumberland Law School in 1975. He is now recognized for his lifetime of service, courage, and achievement as a lawyer and jurist by induction into the Alabama Lawyers’ Hall of Fame.

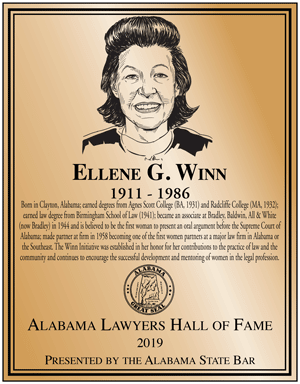

- Ellene G. Winn (1911-1986)

-

Ellene G. Winn was one of the key women in this country who led the way for other women in the field of law. Yet law was not her first love—Shakespeare was. Ms. Winn received her undergraduate degree at Agnes Scott College, and her master’s degree at Radcliffe College, and intended to pursue her PhD in English Literature with a concentration in teaching or writing and a specialization in Shakespeare. But the Depression intervened and derailed her studies. She began work in Birmingham and then started studying at the Birmingham School of Law.

Ellene G. Winn was one of the key women in this country who led the way for other women in the field of law. Yet law was not her first love—Shakespeare was. Ms. Winn received her undergraduate degree at Agnes Scott College, and her master’s degree at Radcliffe College, and intended to pursue her PhD in English Literature with a concentration in teaching or writing and a specialization in Shakespeare. But the Depression intervened and derailed her studies. She began work in Birmingham and then started studying at the Birmingham School of Law.She was a member of Phi Alpha Delta, a fraternity dedicated to promoting high standards of scholarship, professional ethics, and achievement. She distinguished herself at the law school and graduated in 1941—the year the United States entered World War II. With most men off to fight, women were beginning to take on positions in areas that had previously been undertaken predominantly by men.

Ms. Winn broke the gender barrier in 1944 when the Bradley Law Firm (then called Bradley, Baldwin, All and White) hired her as an associate. However; when she was given the position, she was informed that the return of male associates from the war would cost her the job. It did not. She developed an expertise in the area of public finance. She was a creative lawyer, innovative in resolving complex issues in public security cases and actually created new approaches to public finance. She played an integral part in Rogers v. City of Mobile, the 1964 Alabama Supreme Court case that did much to insure the financing, construction and operations at the Port of Mobile, creating a wharf, wharf access bridge and storage facilities with revenue bonds and lease backs.

Ms. Winn was also critical to the creation of the Alabama Industrial Development Authority when she was able to successfully defend its constitutionality as an independent corporation in Edmondson v. State Industrial Development Authority in 1966.

She is also believed to be the very first women to present oral argument before the Alabama Supreme Court.

Her impact was so great, and she was held in such high esteem that the Bradley Firm created the Winn Initiative. It is a program that is dedicated to enhancing the engagement, development, advancement and success of the firm’s female attorneys through mentoring and training sessions in leadership and work-life balance.

In answer to questions from the Wall Street Journal regarding her experiences with sexual discrimination as a female lawyer, Ms. Winn responded that she never experienced sexual discrimination—that she was always treated with the greatest respect. Respect, obviously well earned.

Ms. Winn died on May 1, 1986 in Birmingham, Alabama.